She Taught Me Touch

I grew up in an

imaginary city. Some cities remain the

same for decades, even centuries, but not mine.

The grid of streets I lived on in northwest Detroit remains, but the

neighborhood, the school, the park, the corner store, the incessant hum of

traffic, the Tigers game wafting from every back yard on a summer evening,

those are gone. As a result, my

childhood seems to be a dream or a play whose set long ago burned down.

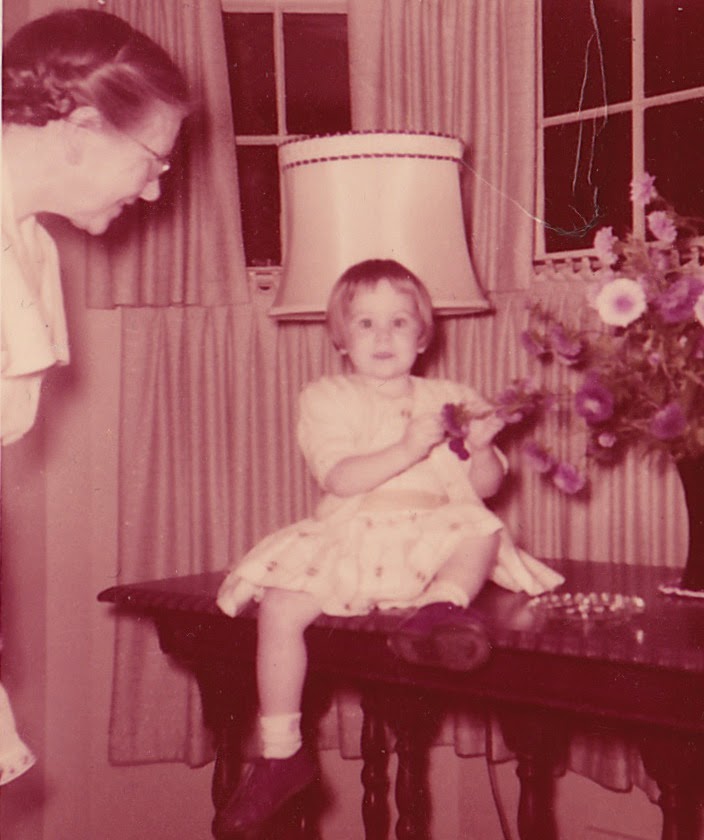

In my memory it’s always warm, an Easter

morning. I am four, wearing a new yellow dress with a white piqué

pinafore. I am standing beside her

house, in the sharp smell of warm brick, the scent of new cotton, vinegary

aroma of Easter eggs. My little brother,

with his quiff of pale hair and his matching yellow suit, looks like a

newly-hatched chick. In my basket is a

pink stuffed rabbit; in his, a blue one.

We are posing for pictures. Or maybe

it’s a summer evening, shadows softening the outlines of my grandmother’s

flowerbeds and making a blue oval in the shade of the oak tree. She is leaning

back in an Adirondack chair, her small, narrow feet in their black lace-up

shoes neatly placed side by side.

She wore rimless spectacles, cotton print

dresses and aprons trimmed in rick-rack.

She cooked pot roast on Sundays, and dotted her side tables with

figurines and bowls of flowers. My memories of her are mostly tactile: her soft

cheeks, her arthritis-cramped fingers, the soft cables of her yellow cardigan,

the nubby surface of her green sofa cushions.

I remember the sound of her voice

as she moved from task to task but I don’t remember her opinions because she

never weighed in on family discussions of politics or religion.

My parents embraced the aesthetic we now call

mid-century modern—Mad-Men style, with its clean lines and rejection of

clutter. At home, our chairs were

covered in naughahyde. Biomorphic

ceramic ashtrays were the only ornaments on our streamlined coffee table. My father, who had spent the war years in

England, hung architectural engravings on the walls and read Evelyn Waugh.

My tall, elegant mother eschewed makeup,

jewelry, lace and frills for herself and for me as well. I had a short haircut and wore sensible

lace-up shoes with my school uniform. At special occasions like Christmas and

birthdays, my grandmother always wore red nail polish, bright red lipstick, and

pearls in her ears. By the end of the

evening, I would have donned her earrings and her cardigan as well as a touch

of the lipstick. In all the festive

snapshots, I’m the short-haired kid in glasses, wearing pearl earrings, an

over-sized cardigan, a smear of red blurring her big grin.

My grandmother’s way of life,

rooted in a childhood on a Michigan farm, was very different from my parents’

austere urban modernism but to me it was a sensory paradise. I can still see the bright yellow tiles on

her kitchen floor and the faded pinks of the cabbage rose print in her

chintz-covered armchair. Once a rich

auburn, her waist-length hair had greyed to a soft gold-pink. In the morning, I loved to watch her pin her

braids into an oval at the back of her head.

I loved to sit by her side, whatever the task. I can still feel the smooth weight of the dull

gold cotton sateen that she used to sew the pleated curtains for her the bay

windows. My grandmother and I stroked

the gold sateen together, admired it, and made plans for every scrap.

Some of the left-over fabric would

become pin-tucked throw pillows for her sofa, and a bit more would appear as an

elegant opera coat for my doll, Lily Goldbell.

On long summer afternoons, she’d weed and harvest fruits and vegetables

in her long back yard that seemed to me a world in itself, with its raspberry

patch, tomato plants bristling in the sun by the pungent compost heap, its

goldfish pond in the shade of the huge oak tree, and nearer the house, beds of

pink cosmas, snowy allysum, black-eyed susans, orange dahlias, gold-and-brown

marigolds.

When the work was done, and the new

potatoes were soaking in ice water, we would sit on the side of her bed and

sort out the top drawer of her dresser, the scarves and gloves and jewelry

boxes. Every object had a story, and as

she told me the story, my grandmother and I would study the beads or try on the

gloves with their three fanned lines of stitches, one for each long bone of the

hand. I would hold a silk handkerchief

to my cheek or run the beads through my fingers of the rosary I’d receive on my

first communion. I’d touch the brooch

waiting for my twenty-first birthday to my collar. I felt as if my grandmother’s dresser held

my whole future safe behind its curved mahogany drawers.

Unlike her sisters, my grandmother

had married young and never went to college. The newspaper sitting in a basket

in her sun room was the only reading material in her house. She never asked about my grades or my reading

level. I was a bookish little girl,

proud of my spot near the top of my class, but I was always glad to leave my

school accomplishments behind when I visited Grandma. Perhaps that was the reason I needed to check

in with her frequently. I longed for the

smells and sights of her kitchen, her knick-knack shelf, her embroidered hand

towels and starched curtains. I begged

to stop for a visit whenever we passed her street corner in the car, no matter

how urgent my parents’ errand might be.

She always had time. When my mother, distracted with two younger

children, was too busy to show me how to do up the buttons on my bride doll’s

elaborate gown, Grandma would sit beside me, and together we would do and undo

every tiny pearl bead, and then we would pin up the bride’s long hair and place

her veil perfectly. Together, we stroked

the delicate tulle and arranged its stiff folds.

When I was five, my grandmother

taught me to crochet with white cotton thread and a steel needle. I am left-handed, so not only did she have to

convey the complex movements to my short, fat fingers and short attention span,

but also patiently transpose all the movements from the right side to the

left. So gentle was her teaching method

that without any struggle, I soon found myself making intricate doilies, much

to the amazement and bewilderment of my mother. With my growing collection of doilies, I

began to understand the geometry of radial symmetry as circles grew with the repetition

of eight spreading petals. From that

moment, working out my grandmother’s patterns for cotton stars, I learned that

holding a needle and thread or a strand of yarn could become as natural as

holding a pencil.

As my school years continued, I

spent less time with my grandmother.

Weekends were devoted to nature hikes with my two younger brothers and

visits to art museums, softball games and old movies on television. I spent my after-school hours inhaling books

in the local branch library, sneaking from the children’s room into the adult

section, and curling up in a corner with Katherine Mansfield, Charles Dickens,

and F. Scott Fitzgerald.

My grandmother became ill. The diagnosis was hardening of the arteries,

but the symptom was an increasingly severe dementia. Her beautiful hair was cut short, and then

her words stopped altogether. When she

died I was fourteen on the cusp of fifteen, just out of my freshman year of high-school,

self-centered, moody, and anxious to put all signs of childhood behind me. No longer interested in doilies, I was busy

reproducing the latest mod styles on my new sewing machine. I wore pale-pink lipstick, and when I could

get away with it, lavender eye shadow and mascara. Beyond a vague sadness on the day of her

funeral, I didn’t grieve or even think much about my grandmother for years

until one Saturday night when I was mid-way through college.

I was sitting at a movie theatre

downtown with my roommates, watching the cult hit Harold and Maude. Ruth Gordon in her seventies looked naggingly

familiar. Suddenly she opened a drawer,

turning to her young co-star Bud Cortt, and said, “let’s see what we have

here.” I began to sob and couldn’t stop until long after the closing credits

rolled. Suddenly, I was back in my grandmother’s

bedroom, poring over her dresser drawer, carefully smoothing each scarf, each

pair of gloves.

At that moment, my link to my

childhood was restored. The sights and

sounds and especially the textures of my childhood came to life again. I connected, consciously, with my past. I

understood that an essential part of me experiences the world, not through

logic or reason, but through my senses.

I remembered how satisfying it was to hold a skein of cotton in my

hands, and I realized why I loved to knit.

Today, forty years later, knitting

still connects me to my grandmother’s love of the actual, material world, her

quiet acceptance of the rhythms of nature, her skill in manipulating needle and

thread, and her rare ability to find eternity in a summer afternoon. The feeling of a strand of yarn comforts me

in a way that no photograph can do. It’s

a direct link to that unspoken, tactile connection, my wordless genealogy, that

imaginary place I discover again every time I cast on and make a stitch.

3 comments:

شركة تسليك مجارى بخميس مشيط

شركة الفارس كلين

شركة مملكة الفرسان

Post a Comment