Last week I plunged in to a project that has scared me for months. I had fallen in love with the Celestarium Shawl featured in Twist Collective for Winter 2012, a circular shawl that replicates a star chart, with the stars represented by yarnovers and crystalline beads. I selected my yarn, a deep blue, I located and collected the beads, and laid the supplies, including the needles, on my work table. And then I got scared.

This is a lace pattern I can’t memorize because it has no

repeats. There won’t be much automatic

pilot knitting here. Instead, I will be

following chart after chart and really concentrating on my work. Lately, I have been knitting in front of my

television screen, catching up on all the past seasons of Breaking Bad, and

cranking out simple scarves, and I don’t know if I can reform my lazy ways any

more than Walter White can turn away from cooking meth.

But last week I read a wonderful little book by Phillippa

Perry, an English psychotherapist, entitled How to Stay Sane. For a psychotherapist, she herself sounds

remarkably good-natured and unflappable.

As I perused her chapter on Stress, I was surprised to see that Perry

recommends a certain amount for sanity and suggests that we make a chart of

things we would love to do, but remain outside our comfort zones. After completing my chart, I could see that

my star-chart shawl was sitting just a little outside the cozy solar system of

my knitting comfort zone. Clearly, it’s

time to tackle Celestarium.

The first step is winding my skeins of yarn into balls. Simple, but not this time. The yarn I chose, as I discovered when I

desperately searched the internet, (not the yarn called for in the pattern) is

notorious for tangling. I found myself

with a tangle more thorny than any I had encountered in all my years of

knitting, and that’s saying a lot.

When I was younger and more impatient, I might have lost my

cool completely and either broken the pesky strands, cut them, or thrown the

whole mess away, but now I can see that of the sources of dismay and

frustration in my life, this little skein of yarn doesn’t rate at all. Instead, I’ve been sitting on the floor,

listening to classical music streaming on my i-pad, and putting in an hour or

so of winding every evening. When the

hour is up, I feel strangely at peace, even though I may have straightened out

only a small number of the hundreds of yarns of wool still tangled on the back

of my chair, and my spine feels like someone inserted an old broomstick into my

back.

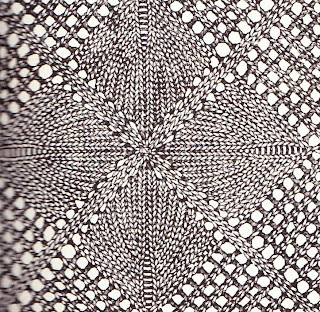

It’s not true meditation, because I’m not trying to empty my

mind or count my breaths, but it is very calming to focus on freeing a

navy-blue thread from its crazy course over and under and around its fellow

strands, reducing what looks like visual cacophony to a single theme, sweetly

turning round and round a little globe:

I hope this first stage in my adventure outside my knitting

comfort zone is a sign that as I go, I will continue to make discoveries. That’s what travel, whether through the night

sky or just through my little life, is all about.